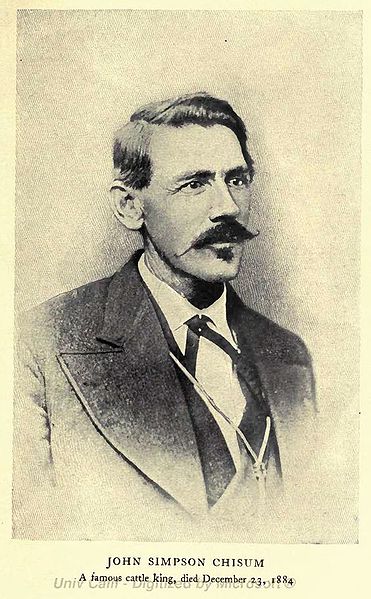

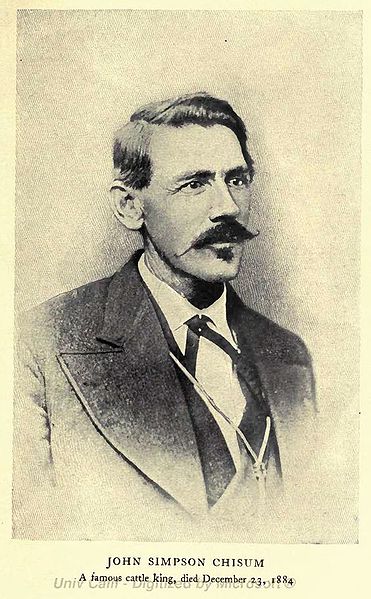

John Chisum — Cattle

King of the Pecos

Although Juan

de Onate is credited with bringing the first cattle into New Mexico from old Mexico, it was John Chisum

and men of his ilk who made the cattle industry an economic force in the 1860s.

Original

buildings at the South Springs Ranch

Chisum was a Texas bachelor in his early thirties.

However, there were rumors, later proved to be true, that he had a love affair

and two daughters by a mulatto slave girl. He had purchased her for $1400

from some emigrants bound for California. Jensie was

an excellent housekeeper and cook, only fifteen and beautiful. At the outbreak

of the Civil War, Chisum freed all his slaves,

including her. He then put her and the girls in a home in Bonham, Texas and left funds for their needs.

He blazed the historic Chisum Trail from the little town of Paris, Texas, where his cattle herd was first

begun, across the desert of Texas then north to the Pecos Valley in southeastern New Mexico. Tales have varied about how many

cattle were in the drive in 1867 when he took them to Fort Sumner. Some say 600, some say 900. Author Georgia B. Redfield in

an article in The Cattleman about 1942, describes the trip:

“Although it was early spring, it was

as hot as any mid-summer day of the year 1867 when nine hundred head of gaunt

beef cattle staggered over an unbroken trail, on the last lap of a three-day

waterless drive...’They won’t ever make it to Sumner,’ said one of the

cowboys...’We’ll make it,’ replied the dauntless Chisum

with a grim tightening of the tired lines of his mouth and jaw, which in every

crisis of his life characterized his refusal to accept defeat.”

The campground and cattle rest

established near the Rio Hondo and Rio Pecos, now the site of Roswell, provided much needed water.

Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving

were also cattlemen driving cattle to Fort Sumner. When Loving succumbed to a wound from

a bow and arrow in 1868, Chisum and Goodnight formed

a partnership. In the next five years Chisum earned

enough capital to move permanently to New Mexico.

He purchased South Spring Ranch,

with its 40 acres, the South Spring and a large adobe house, three miles south

of Roswell. He tore down the old adobe and built

an adobe/frame house with four rooms on each side of an open hallway.

Underneath the open hall there was an acequia. There

were verandas on both the front and back of the house so he could sit in the

shade at any hour of the day. He built a separate room at the back of the house

for his cowpunchers to hold their dances so “they don’t beat up my Axminster carpets with their boots.”

Described as a man born to the land and

handsome, he was average height but strong and with a sunburned and weatherbeaten complexion. His hair was thick and brown, his

eyes a blue gray, and he wore a mustache. He was known to be fair in his

dealings with others, one who paid his debts and wasn’t involved in any

violence.

The first brand he used on his cattle

was “the long rail," a straight horizontal line across the whole

side of a cow. However, it was easily changed to other brands so he used a

large “u” on the shoulder of the cows. But his “jingle bob” brand

was the most famous in the west. It was a slit on the cow’s ear with one

part of it standing upright and two-thirds of it bobbing. The Cattle King

was said to have remarked, “Them derned ears won’t

jingle but they sure will bob.”

He grazed 80,000 head of cattle on a

one-hundred mile stretch of public domain. As homesteaders began to arrive in Roswell to start small cattle operations using

the public domain for grazing, these cattle became mixed in with the Chisum herds. This caused extra work at round-up time as

well as opened the door for cattle rustling. Chisum

was possessive of his turf, and there were hostilities.

This conflict was one of the elements

contributing to the Lincoln County Wars. John Chisum

preferred to make his contacts directly for the purchase of beef for Fort

Stanton rather than go through Lawrence G. Murphy, beef subcontractor for a

Santa

Fe

government contractor. Murphy had virtually held a monopoly until 1877 when Chisum backed new residents Alexander A. McSween and John Tunstall. The

three of them opened the county’s first official bank.

McSween’s business partner Tunstall

was killed in a brutal ambush by a sheriff’s posse. That was followed shortly

by the killing of two of the men accused of killing Tunstall.

A state of near anarchy now existed in the huge county of Lincoln. The battles continued until

1881. Chisum was never directly involved in

them although he gave sanctuary and material support at his South Springs

Ranch.

Shortly thereafter Chisum

came down with small pox. His men put him in a tent in the camp south of the Pecos, assigning men to nurse him day and

night. A black cowboy, Frank Chisum, his friend, and

almost considered a son, rode to Fort Stanton to bring him medical help. Frank

stayed with Chisum until he was well, then came down

with the disease himself but also survived.

In 1883 a tumor began to grow on Chisum’s neck, causing him pain. He tried to remain

optimistic but knew his father and grandfather had died from cancer. Finally in

1884 he decided to go to Kansas City for treatment but took only a driver

with him. On July 24 surgeons removed the tumor. When he was told the operation

was a success he started for home. In Las Vegas, New Mexico, he fell ill and was advised to go to Eureka Springs, Arkansas to a health spa for further care. He

lived in a hotel there for several months. However, the tumor returned even

larger. His brother James came to stay with him in December and on December 22, 1884 Chisum died. He was buried on

Christmas Day at the family plot in Paris, Texas.